You're standing in line at the DMV for the third time this month with the same paperwork and the same questions. A different person asks you to fill out the same form again because the last department didn't forward it properly, and two hours of your life are gone. You're not getting service - you're experiencing waste.

This isn't incompetence, it's broken process design. Every organization has workflows that look productive but accomplish nothing, like forms that get forwarded six times before anyone reads them, or meetings that exist because someone scheduled them five years ago and nobody questioned it. Most systems get designed around internal convenience instead of actual outcomes.

Business process analysis exists to identify and eliminate this waste. The method comes from Toyota's production system, refined over decades of manufacturing work, and the core principle is direct: separate activities that create value from activities that just create work.

Three Categories of Work

Value-adding activities produce something a customer would pay for, and the test is straightforward. Would a customer agree this step is needed and be willing to pay for it? If you removed this step, would the customer notice the product is worse?

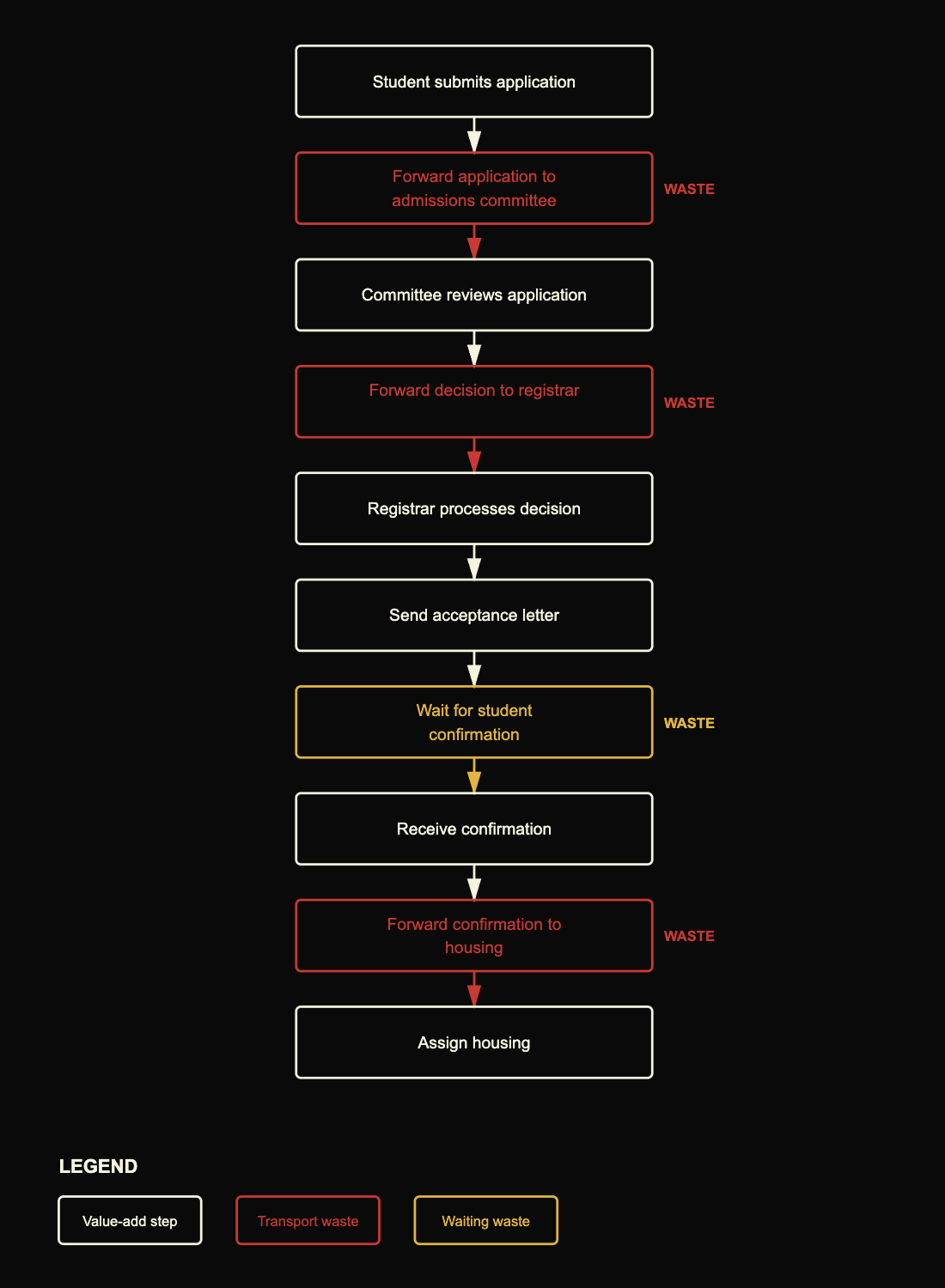

Order fulfillment that confirms delivery dates, assembles products, and ships them on time is value-adding because customers pay for that outcome. University admissions that reviews applications and makes decisions falls into this category too since students pay tuition for that evaluation.

Business value-adding work supports operations without directly touching the customer. Financial reporting, compliance documentation, and payroll processing are things customers don't care about, but the business can't function without them. They're overhead, but necessary overhead.

Everything else is waste - forwarding emails between departments, waiting for approvals, correcting defects from earlier mistakes, re-entering data because systems don't talk to each other, manual handoffs between teams, context switches between tasks. These activities consume time and resources while producing nothing.

Here's the pattern you'll notice: anytime work is manual, it's probably not value-adding. Manual data entry, manual approval routing, manual quality checks that automation handles better - these steps exist because someone built a process around human limitations instead of designing for efficiency.

Seven Sources of Waste

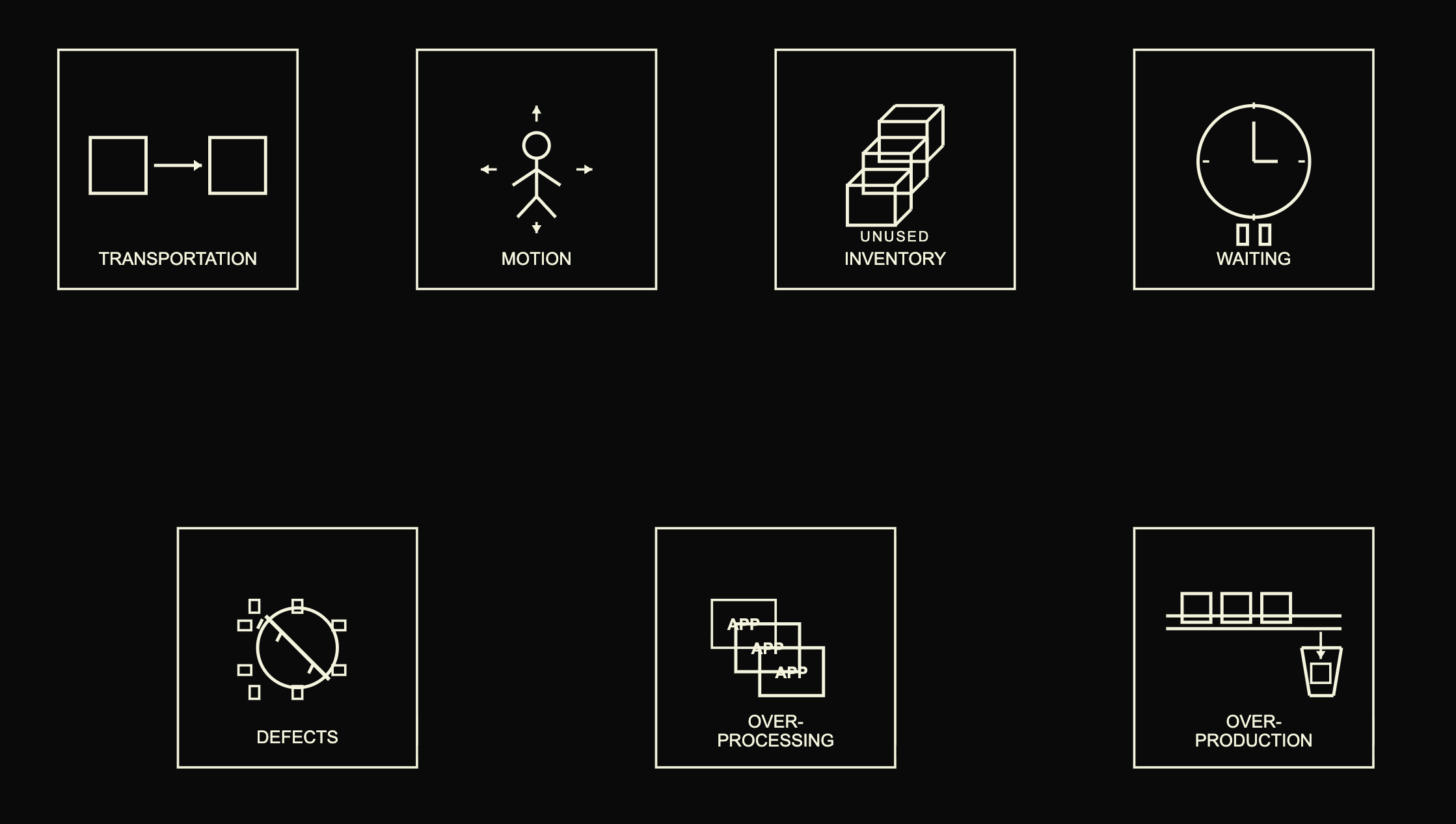

Toyota identified seven sources of waste in manufacturing, and the model applies way beyond factory floors. Three categories involve movement, starting with unnecessary transportation that moves materials or information between locations without transformation. Forwarding purchase orders to warehouses or sending admission results between committees creates handoffs that add delay and error risk.

Unnecessary motion means workers or data move more than needed to complete tasks, like switching between applications or walking to different offices for signatures. Each movement wastes time without adding value to the final product.

Inventory holds materials, information, or work-in-process that isn't being used. Physical materials sitting unused, work-in-process piling up between stages, information gathering dust in databases - each represents capital tied up producing nothing while the organization pays storage costs.

Waiting happens when materials, data, tasks, or people sit idle, and nobody's productive while the clock runs. Manufacturing waits for materials, software development waits for code reviews, hiring waits for approval signatures. The cost stays the same regardless of industry.

Defects require correction, rework, or compensation when someone has to redo work that should have been right the first time. Re-sending order confirmations because the first one had errors or receiving rejected products back from customers creates rework loops that destroy productivity silently.

Over-processing performs tasks beyond what the outcome requires through unnecessary perfectionism. Three approval layers when one would suffice, six rounds of editing on an internal memo, executive approval for routine purchases - each refinement costs time and money while returns diminish quickly.

Over-production creates outcomes nobody needs, like reports nobody reads or features nobody uses. Processes run because they've always run, not because they serve a purpose. These activities feel productive because people stay busy, but they accomplish nothing because the output has no consumer.

The Boeing Lesson

Boeing learned this the hard way when they implemented lean management principles from Toyota's playbook to cut inventory, reduce cycle times, and eliminate redundancy. Sounds good on paper, but execution failed catastrophically.

Quality dropped, defect rates climbed, and safety issues emerged. The problem wasn't the lean method itself - the problem was implementation. Boeing eliminated steps that seemed redundant but actually provided quality checks, cut inspection procedures that caught defects before assembly, and optimized for speed without maintaining verification systems.

Toyota runs pilot tests before full deployment because small-scale experiments reveal what works and what breaks. Incremental scaling lets you fix problems before they multiply, but Boeing skipped this step. They went from concept to company-wide implementation without validation, and the result cost them billions in recalls, delays, and reputation damage.

The lesson isn't that lean management fails - the lesson is that cutting waste requires understanding what's wasteful. Not all redundancy is bad since some double-checks prevent disasters, and some "unnecessary" steps catch problems before they become expensive.

Applying This

Map any process you touch from start to finish and identify each step. Ask three questions: does this create customer value, does this enable business operations, or does this just create work?

Eliminate pure waste first - handoffs between departments, approval layers that rubber-stamp decisions, forms filled out because forms have always been filled out. These cuts hurt nobody and free resources immediately.

Reduce business value-adding work next by automating what machines handle better and simplifying what can't be automated. Question whether each requirement still serves its purpose since regulations change and business needs evolve, but processes don't keep pace.

Optimize value-adding work last because these activities directly create outcomes. Don't cut them - make them faster, cheaper, or better by removing friction, improving tools, and training people. Never sacrifice quality that customers pay for.

Start small by picking one process you control. Document current state, measure time, cost, and quality, then identify waste sources. Design improvements, test changes on limited scope, measure results, and scale what works while killing what doesn't.

Five percent efficiency gain repeated across multiple processes transforms operations, and most organizations have enough waste to cut 20 percent of work without losing output. The gains compound over time.

Stop accepting waste as normal and question every step. Eliminate what doesn't matter because the goal isn't perfection - the goal is continuous improvement. Each iteration teaches you what works in your context, and each reduction in waste frees resources for value creation.

Don't be Boeing by testing before you scale and learning before you commit. Start somewhere, improve something, and repeat.